By Martin Thornton

PART ONE

There is good reason for dividing this lecture into two unequal parts. I must first offer a brief resumé of what I take the Anglican spiritual tradition to be; then I should like to look rather more fully at the contemporary impact of our tradition, concluding with a somewhat dangerous game of attempting to read the signs of its future unfolding.

Pedantic haggling over the meaning of words is not the most exciting exercise, but it is apparent already that some attention must be given to that most ambiguous and abused term “Tradition”; paradosis, traditio, literally a giving-over, or handing-over. Handing-over be it noted and not handing-down.

To the Fathers of the primitive Church, Tradition was almost synonymous with Revelation; it consisted of the saving acts of God in Christ—the incarnation, passion, resurrection and ascension—in other words in the Creeds to come, which were “handed-over” to successive generations. To be traditional was to be consistent with Divine Revelation: and this still pertains. Tradition is defined as “the continuous stream of explanation and elucidation of the primitive faith.” To Bishop Francis White it is “derived from the Apostolical times by a successive current.” Hundreds of additional references could be added, and many with the paramount simile of the river, as “stream” and “current” in those given above. Tradition, then, is a living stream, a flowing river, and not a stagnant pool; it is something that moves. Tradition should never be confused, as it often is, with antiquarian nostalgia.

Neither should tradition be confused with custom. Visitors to England may have discovered the tradition whereby the crown jewels are displayed in the Tower of London guarded by the Yeoman dressed in Tudor uniform and armed with pikes. But the Yeoman of the Guard are customary; the real tradition is carried on by a plain-clothed cop sitting in the corner with a gun.

“Anglican” spirituality is often confused with, and even confined to, that which issued from the teaching of the Caroline Divines—which is why I prefer the adjective “English,” despite its insinuation of insularity.

Nevertheless, for elucidation of this tradition, the seventeenth century is a good starting point, not because it is the beginning but because it forms a fulcrum; a point from which we can look back as well as forward. And this precisely because it is the Caroline method; they began by looking back to the New Testament and patristic roots, yet it was a golden age of future expectation. Anglicanism ever refutes the notion that is a sui generis seventeenth-century invention, but rather that it is the result of continuous historical development. The seventeenth century may indeed be seen as the first full flowering of our tradition; a glorious new bloom that, like any pure breed, is derived by careful selection and cross-fertilization. Anglicanism has a pedigree going back to the New Testament, a spiritual lineage derived from the accumulated wisdom of the past.

What are the constituents of this pedigree? I have tried to trace it in some detail in my English Spirituality; here it must suffice to take a fleeting glimpse at four main areas.

(1) The first Christian millennium was largely dominated by the formulation of theology, and of liturgy in which it found expression. Following John Macquarrie, theology may be defined as the Church reflecting upon and clarifying its experience. It is significant that the Caroline Divines were so especially concerned with this period of creedal formulation, and outstandingly learned in patristic theology from both East and West. But the key Anglican authorities were, and still are, Saint Augustine and Saint Benedict.

(2) Saint Bernard of Clairvaux dramatically changed the emphasis, initiating an upsurge of affective devotion of a largely personal kind, centered upon the living reality of the Sacred Humanity of Jesus. Devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and extra-liturgical cultus centered on specific aspects of the Passion, followed logically. A sane and disciplined emotionalism entered into Christian prayer.

(3) The absolute heart of the English-Anglican tradition is a constant attempt to synthesize these two poles: intellectual and affective, reason and emotion, corporate and personal, the head and the heart. And so if its Patriarchal founders are Saint Augustine and Saint Benedict, with a still living influence from Saint Bernard, the more immediate father-founder of Anglicanism might be seen in the tremendously significant figure of Saint Anselm. Thereafter influence is exerted by the later Cistercians, the School of St Victor in Paris, the Canons Regular of St Augustine, the Friars mInor, and the Thomist, rather than the Rhineland side, side of the Dominican movement.

(4) So to the universally acknowledged “English” School of the fourteenth century, embodying as perfectly as may be, this intellectual-affective, theology-devotion synthesis. The Revelations of Juliana of Norwich is probably the best example, and almost certainly the best known of all the fourteenth-century writings. It is a disturbingly vivid expression of affective devotion to the Sacred Humanity of Jesus; some would say veering toward feminine hysteria. But that is to miss the deep underlying current of trinitarian, christological and atonement theology that underpins each paragraph.

If this is the most obvious popular expression of the ideal its supportive ascetical direction is to be found in Walter Hilton’s Scale of Perfection. Published in 1494 it continued to be reprinted up to 1679. The strong suggestion is that it continued to be the English clergy’s Vade Mecum, throughout and beyond the Reformation period. Legislation can be brought to bear on liturgy, ritual and ecclesiastical polity; social and political upheaval can change the superficial face of the Church overnight, but deep-seated personal devotion is less tractable. The transference from the medieval Latin Mass to Cranmer’s first Prayer Book took one week, but it is unlikely that the Englishman’s prayers changed all that radically from the first to the third of June 1549. Neither is it likely that English spirituality became suddenly Puritanical in 1552. It is more than likely that the influence of Hilton survived throughout.

And so to the fulcrum and watershed of the seventeenth century; the consolidation of a millennium of development. What are the fundamental characteristics of this germinal School of Prayer? There are again four distinguishing factors.

(1) The synthesis of theology and devotion, heart and head, sublimely achieved in the fourteenth-century, remained the ideal: “true piety with sound learning”—”with” not “and”!—became the Caroline motto. But in an age of theological re-formation, of a searching for the primitive tradition, and with radical liturgical revision, it was almost inevitable that the theological head took precedence over the devotional heart. And I suggest that this situation is still with us; the Anglican ideal remains but not wholly fulfilled. Our history since the Caroline age, or more strictly since the fourteenth century, has been made up of attempts at the ideal only partially achieved by a series of swings of the pendulum. Like the Carolines we are still over-intellectual, suspicious of religious experience, unhappy with “enthusiasm,” a little frightened of the human emotions. Caroline thought degenerated into Deism, the Evangelical Revival of the Wesleys restored the balanced, further rationalist reaction was countered by the Oxford Movement, which may have achieved the balance better than anyone since Juliana and Hilton: true piety with sound learning. But was it piety founded on the wrong model?

(2) The second integral Anglican characteristic is its insistence on the unity of the Church. In the Caroline period there was no gulf between priest and layman, no screened-off division between the sanctuary and the nave. There is another irony in that the doctrine of the Church was central to both the Reformation and the Oxford Movement, yet the Caroline ideal has never quite been achieved since: except, possibly, today.

Corollary to this emphasis was a deeply domestic spirituality; foreshadowed in the twelfth century by the glorious, and so English, foundation of Saint Gilbert of Sempringham, and typified five centuries later by Nicholas Ferrar’s Little Gidding. But it was the fourteenth-century English writers who invented the subtle and deeply significant term “homely”: Margery Kempe enjoyed “homely dalliance with the Lord”; Juliana’s “homeliness” hints at Baptismal incorporation into the Sacred Humanity, therefore habitual, constant, stable, and in the deep contemplative sense, simple. Homeliness points to that form of contemplative prayer wherein one is united to God through a harmony with his creation; it has links with the recapitulation theory of Saint Irenaeus, with the method of Hugh of St Victor, and it is strongly developed in Juliana.

Less technically, the idea spills over into Caroline devotion as more down-to-earth domesticity; the source and setting for Christian life and Christian prayer is the village, the farm and above all the home, not the oratory or shrine: it is a Benedictine ideal. Of all the classical analogies describing the Catholic Church, Anglican spirituality favors the “Family of God”: Onward Christian Soldiers is an eccentric deviation from Anglican hymnody.

(3) Symbolic of this emphasis on the unity of the Church, with its domestic spirituality, is the extraordinary weight of authority given by the Caroline Fathers to the Book of Common Prayer, from 1549 onward, and further up to 1928. It is customary for Benedictines to read selections from the Rule at silent meals, the Ignatian exercises still form the heart of Jesuit spirituality; but no school of prayer has been so firmly tied to a book as the Caroline Church of England. “Bible and Prayer Book” were the twin pillars of this spirituality, with the later given almost equal status, and subjected to the same kind of systematic study as the former. The Book of Common Prayer was subjected to annotation and commentary with not a rubric, colon or comma regarded as insignificant.

It is again necessary to look at the historical setting, for the Book of Common Prayer is derived from a long line of ancestors, ultimately from the Benedictine Regula, with which, ascetically, it has much in common: both are designed to regulate the total life of a community, centered on the Divine Office, the Mass, and continuous devotion as daily, domestic life unfolds. Both are concerned with common, even “family” prayer. Neither are missals, breviaries or lay manuals, because here the priest-lay division does not apply: they are common prayer, prayer for the united Church or community.

The vital principle, tragically missed by both modern liturgists and their critics, is that, like the Regula, the Book of Common Prayer is not a list of Church services but an ascetical system for Christian living in all of its minutiae.

To the seventeenth—or indeed nineteenth—century layman the Prayer Book was not a shiny volume to be borrowed from a church shelf on entering and carefully replaced on leaving. It was a beloved and battered personal possession, a life-long companion and guide, to be carried from church to kitchen, to parlor, to bedside table; equally adaptable for liturgy, personal devotion, and family prayer: the symbol of a domestic spirituality—full homely divinitie.

(4) From all this there emerges a Moral Theology of much originality. The majority of Caroline casuists—for that is what they all were—advocated auricular confession, but the emphasis changed from the application of juristic rules to the training of the individual conscience, toward moral maturity and personal responsibility. Caroline Anglicanism is Christianity for adults. This moral theology was not calculated by clerical professors in the universities; it was hammered out in the pulpit. And it was domesticated: the juristic distinction between “mortal” and “venial” sin became a pastoral difference between sins of malice and of infirmity; grace was the loving power of a present Redeemer, never mind the hair-splitting distinction.

PART TWO

I began by defining tradition as that which moves; it is not antiquarian nostalgia, but a synthesis of past, present and future; a flowing river not a stagnant pool. Tradition has its source, its roots, in the past, but it continues to develop and re-form (never forget that what happened to Anglicanism in the sixteenth-century was not so much reformation but re-formation). Tradition begins with the present and looks both ways; to the wisdom of the past and to future development.

So what of the present? What of the future? What are the signs of an unfolding tradition? Prophecy is a risky business, but there are four factors that might be worth looking at:

(1) I have pointed to the central Anglican ideal, traceable at least to the teachings of Saint Anselm, and perfectly expressed in the fourteenth-century English School: the head-heart, speculative-affective synthesis; true piety and sound learning. And we have seen how, while upholding that ideal, the Caroline period never quite got in balance; seventeenth-century spirituality was weighted on the intellectual side, at the expense of a proper emotionalism. Despite the Wesleyan reversal, and a brave attempt at righting the balance by pastoral Tractarianism, the over emphasis on the intellect, with a consequent fear of feeling, has characterized Anglican spirituality ever since.

The last two decades have witnessed three very significant signs of reaction, inevitably over-reaction, but given time, given a little more theological underpinning, something to be welcomed.

(a) The 1960s saw the rise of the “Jesus people.” The Jesus kids to whom the established Church was too dull and respectable by half; to whom the liturgy was formal and lifeless; to whom theology was metaphysical and meaningless. But did they love Jesus! The movement seems to be waning but it should not be dismissed as simply a sentimental bit of childish playacting. While scholars were arguing about the historical Jesus and the Christ of faith; about the historicity of the saving acts of a demythologized gospel: the kids were loving Jesus, and they claimed experience of him in daily life. They were not so far from the Wesley’s “Christ as personal Saviour,” and possibly a bit nearer still to the Cistercian reformers: the Patron Saint of the Jesus kids has to be Saint Bernard. The 1960 brand of this classical spirituality may be dismissed as naïve, brash, adolescent, shallow and immature, but if cultural factors have an ascetical impact, we cannot dismiss Jesus Christ Superstar or Godspell as impious. And it is not entirely without significance that contemporary Christology—the real scholarly stuff—has a good deal in common with those Jesus kids of twenty years ago: in their different ways, both are saying nevermind the Chalcedonian categories, where is the whole, real, resurrected and ascended Lord: the Man-Jesus.

(b) If the Jesus kids rediscovered the real live Jesus, the Charismatics (or Pentecostals or whatever we call this total movement) claim to have rediscovered, or rather to have been rediscovered by, the Holy Spirit. It is difficult to believe, like Elijah to the priests of Baal (1 Kings 18.27), that the Holy Spirit has been asleep for four centuries. It is equally difficult to refute that something quite startling has happened, worldwide and ecumenically, in recent years. Could it be that the Spirit has indeed been active all this time but that the English-Anglican terror of religious experience has failed to respond? But the patient and long-suffering God always wins in the end, so perhaps latterly has has insisted on being heard and received. Such divine breakthrough is apt to cause explosive trouble in a sinful Church, and so there are facets of Pentecostalism that are disturbing and that look very much like heresy; for this the all too stolid Anglican of the past, fearful of the Spirit’s activity, must take a good deal of the blame. If you persist in damming the river you are going to get a flood. Yet Pentecostalism is capable of theological interpretation, and things are settling down. Perhaps the pendulum swung too far, but it is returning to its balanced midpoint; to the head-heart synthesis. Now we have less fear of religious experience, of feeling and emotion; our exaggerated intellectualism is being softened as we return to our true ideal. The present revived cultus of Juliana of Norwich is very significant indeed. Sometimes awkward and embarrassing, but the Charismatics have done Anglican spirituality no mean service.

(c) Caroline theology made much of the Greek tradition. Hooker, Cosin and Beveridge abound in references to Athansius, Basil, Chrysostom and the Cappadocians. But they stuck with theology. A significantly new Anglican movement is a rapidly growing interest in Eastern Orthodox liturgy and spirituality, with its wide range of experience from the simplicity of the Jesus Prayer to a profound creation-mysticism.

These three factors militate against that seventeenth-century tension, fear of experience and exaggerated distrust of the emotions, and so help to restore the doctrine-prayer, head-heart synthesis of true Anglicanism.

(2) That vague and diffuse philosophical stance which is generally known as existentialism is as much a product of sociology as of philosophy; it attempts to describe how modern people think rather than to produce an academic philosophical system, concluding that the contemporary interest is in existence, or experience, rather than in substance. The traditional creeds and formulae upon which spirituality is based are couched in substantive terms, which now need translating into existential terms.

To employ a simple analogy I have used elsewhere, to any modern person a knife would immediately be defined as something you cut things with. Saint Athanasius would define a knift as metal. The latter is substantive thought: what it is composed of. The former is existential thought: what is it for, or how is it experienced; so without ever having heard of Kierkegaard or Sartre, modern people are existentialist.

Modern theology attempts to translate the old substantive categories—what are God’s attributes, how are divinity and humanity united in Christ’s person—into existential terms: how is God experienced? how do we confront the living Christ in the world? Back to the Jesus kids. And this too affects prayer, again by countering the over-intellectualism of the Anglican past and taking a sane but courageous view of religious experience. In personal devotion and liturgy, the substantive view issued naturally in discursive meditation and an insistence on understanding. The existential view looks toward contemplative experience. All of which is added support to a return to the speculative-affective synthesis.

(3) We have noted that the unity of the Church is a basic characteristic of the Anglican spiritual tradition. The Church is one, welded together by the Book of Common Prayer, which will have nothing to do with priesthood as sacerdotal caste divorced and differentiated from the laity. Nevertheless this ideal also has not been constantly achieved. The eighteenth century divided priest and laymen in terms of social status; the nineteen century, under the influence of the Tractarians, returned to the medieval pattern.

The Liturgical Movement has the closest connection with the two previous points. In its present form it seeks to express a unified family of God, in existential or experiential worship. The Central altar, the Westward position, increased lay participation, the liturgical Pax, all point in this direction. There is a certain fear of change, a certain criticism, especially in modern biblical language, and, like the charismatic and/or pentecostal upsurge, the pendulum could have swung too far. But the reaction is a healthy one, against Caroline tension, against deistic rationalism, against artificiality. Yet contemporary liturgy is “traditional” in a way that 1662 is not: it is based on a much profounder liturgical theology, a more respectful and scholarly attitude to the primitive—the English eucharistic rite is now based firmly on Hippolytus, 1662 is based on Cranmer! All of which is very good Anglicanism indeed!

(4) Closely connected with this point (3) is a return to lay participation, not merely in liturgical or administrative aspects, but in the deepest realms of prayer, of ascetical theology, of spiritual direction and of pastoral counsel based on the Gospel (in my own English diocese of Truro the number of lay, and predominantly female, theology graduates is quite extraordinary and wonderfully welcome).

But this raises a problem of authority that is most pertinent to the Anglican tradition. It is well enough known that the English seventeenth century produced a galaxy of lay theologians: Henry Dodwell, Izaak Walton, Robert Boyle, Sir Thomas Browne, Susanna Hopton, Mary Caning, to name but a few of the most prominent. The tradition continues into this century: Dorothy Sayers, Lorna Kendall, and those with a more pronounced American flavor: T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, Dr Dora Chaplin, and doubtless many more of whom I an unaware. But in the seventeenth century such names of repute were supported by a national network of lesser known but efficient laity.

The seventeen century English parish was run by that remarkable partnership of parson and squire, sometimes in loving partnership, sometimes in envious rivalry, co-operating and squabbling alternatively. And yet it was generally understood that if the parson had a general oversight of the spiritual welfare of his flock, the squire had responsibilities for the pastoral care of his household; his family, his servants and his tenants. The squire presided at family prayers, which were based on the Prayer Book offices. His wife and adult daughters visited the sick, distributed alms and care for spiritual development, according to their capacity, which was often more than competent.

This was the pastoral expression of the one united Church, with no great divide between priest and laity, and with every educated layman and laywoman accepting that serious pastoral responsibility which is happily returning. But the structure of Caroline society was such that social position and proven competence carried their own authority. Today we are bedeviled by qualification mania: diploma-itis. Up to around the mid-nineteenth century the qualification for a job—any job from spiritual direction to extracting bad teeth—was one’s ability to do it; now one has to have a piece of paper signifying that you ought to be able to do the job but probably can’t.

Today the Anglican Church has numbers of laity who are wholly competent in spiritual direction and other seriously theological pastoral skills. Very occasionally those to whom they could minister are wrongfully doubtful of their real ability: where is the magic bit of paper? Much more often the lay experts, who humbly know that they can do the job, hold back in anxiety over their authority: they have no bit of paper.

Modern Anglicanism has a straight choice in this matter: it can return to the Caroline ideal of One Church, One Christian community of glorious diversity and spiritual talent; of uninhibited spiritual family talents, father supporting mother, son helping daughter, daughter guiding her brothers, and nephews and nieces joining in: to hell with the bureaucratic, qualifying bits of paper.

Or we can opt for the modern, and curiously also medieval, system of an authorized hierarchy: degrees in theology, diplomas in sociology, licentiates in pastoral counseling, et al. Or, medieval-wise, ordination to the office of deacon, sub-deacon, sub-sub-lay deacon, lector, doorkeeper, sacristan, server, cellarer (I rather go for that one), et al. The medievals meet modern American, contracted from the Germans, in diploma-mania. Now Western Europe, not least England, have caught the disease.

But the Anglican ideal cuts across all this nonsense. Can you, by the gifts God has given you—and please do not commit the blasphemous sin of pretending that he has given you none—help, support, guide and encourage your brothers and sisters in Christ to deeper devotion, adoring worship, creative prayer, redemptive sacrifice; the unleashing of the power of Christ. If you can, or think you can, or by grace you might: for God’s sake get on with it. Never mind the bits of paper.

(I am terribly proud of being a Doctor of Sacred Theology of the General Seminary in New York, but I don’t think I will mention it before the judgment seat of Christ.)

But we must be practical: We do live in a diploma-manic age. The other side of the coin is that we don’t want quacks. At home we have courses in ascetics, in spiritual direction, and our Bishop publishes the names of those who have taken (taken not passed) such courses. This seems a good way out of the present dilemma.

Perhaps a creative synthesis will emerge, as Anglicanism has so often produced in the past—the developing, unfolding, tradition. Our ultimate value is that we believe in God not in ourselves. Via Media has nothing whatever to do with compromise; it has everything to do with spiritual sanity.

END

[This lecture was composed on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Oxford Movement and first published as chapter four in The Anglican Tradition, ed. Richard Holloway (Wilton, Connecticut: Morehouse-Barlow, 1984).]

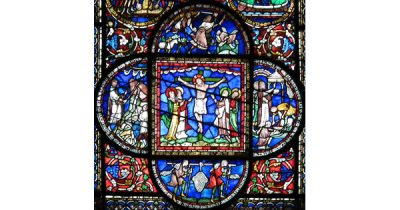

Cover image “Canterbury cathedral-stained glass 13” is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 / Cropped from original